JANA MARTIN received an MFA from the University of Arizona, where she has also taught fiction writing. Her highly praised debut collection Russian Lover and Other Stories is published by Yeti Press. Her story “Hope” won a Glimmer Train Short Story Award for New Writers. Her stories and nonfiction have appeared in Five Points, Spork, Yeti, the Village Voice, Cosmopolitan, and Willow Springs. A veteran of numerous downtown bands including the Campfire Girls, Jana lives in Olivebridge with a large number of dogs, chickens, and pigeons, and is currently writing a novel.

JANA MARTIN received an MFA from the University of Arizona, where she has also taught fiction writing. Her highly praised debut collection Russian Lover and Other Stories is published by Yeti Press. Her story “Hope” won a Glimmer Train Short Story Award for New Writers. Her stories and nonfiction have appeared in Five Points, Spork, Yeti, the Village Voice, Cosmopolitan, and Willow Springs. A veteran of numerous downtown bands including the Campfire Girls, Jana lives in Olivebridge with a large number of dogs, chickens, and pigeons, and is currently writing a novel.

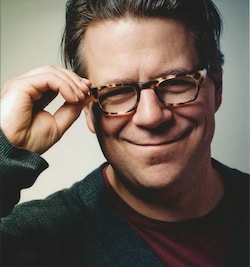

GREG OLEAR (OH-lee-ar) is the founding editor of The Weeklings and the author of the novels Totally Killer and Fathermucker, a Los Angeles Times bestseller. He was Senior Editor of The Nervous Breakdown, and his writing has appeared in The Beautiful Anthology (TNB, 2012), at Babble.com, The Huffington Post, The Rumpus, The Millions, Hudson Valley Magazine, and Chronogram. He has taught creative writing at Manhattanville College, and lives with his family in New Paltz, where Fathermucker is set.

Read Nina Shengold’s Chronogram profile.

“True Fiction” – 10/23/14 – The Exercises

Fiction writers, essayists, and The Weeklings editors Greg Olear and Jana Martin delighted a packed house with readings of Jana’s story “Goodbye John Denver” (from her collection The Russian Lover and Other Stories) and a sneak peek at Greg’s new novel-in-progress (following in the great footsteps of Fathermucker and Totally Killer).

Jana Martin & Greg Olear

Nina and Jana

Our topic was “True Fiction,” which Nina described as fiction that starts with one foot in the truth. Instead of recording what actually happened, the writer asks the question, “What could have happened?” or “What if…?”

Jana said she writes essays and fiction “with two entirely different hands,” and that for her, fiction “comes from a place of yearning.” Greg talked about fiction’s slower pace and “longer shelf life,” saying that if he has an immediate response to something in the culture, it’s an essay. If it requires longer to write, and will last longer, it’s fiction.

Both writers have set stories and novels in places they’ve lived; Fathermucker is set in a pitch-perfect New Paltz, and many of Jana’s stories take place in parts of the country where she’s lived or traveled. Greg commented that he often writes something set in a location from his past while he’s living somewhere else, and finds that distance helpful. Nina sometimes fictionalizes the name of a town, but surrounds it with actual places from the same region. This can give you a strong sense of place without having to adhere to a rigid street map.

All agreed that if you’re using a real location (especially a familiar one, like midtown Manhattan), it’s important to get the details right, but several participants pointed out that too much research can be off-putting, cluttering the text with what Ed McCann called “Wikipedia moments.”

We also talked about modeling fictional characters on actual people. Jana suggested disguising specifics, but basing the character on the truth of a person. At some point, she said, “The character owns you. Fiction allows characters to swell outside their outlines.” Greg added that writers have no idea how people will respond to seeing a character based (even in part) on themselves–sometimes the person you’ve flattered gets offended, and the one you’ve made into a villain is delighted. He quoted Faulkner’s dictum that “if a writer has to rob his mother, he will not hesitate; the “Ode on a Grecian Urn” is worth any number of old ladies.”

GREG’S EXERCISE:

Write a paragraph from the point of view of a character returning to the hometown he or she loved. Now write a paragraph from the point of view of a person returning to the hometown he or she did not love.

JANA’S EXERCISE:

Write a scene in first person, present tense about an extremely uncomfortable encounter with a second character (characters can be real or invented). How does it feel to be in proximity with that other person? What happens?

NINA’S EXERCISE:

Write a seven-sentence narrative in which the first sentence is entirely true, and the seventh is entirely fictional. The shift from truth to fiction can come at any point between, in small increments or with one bold decision. Can the reader guess where the changeover happened?