April 30, 2015

My guest this week was the astonishing Porochista Khakpour. After she read several excerpts from her visionary novel The Last Illusion, we sold every copy on the table, and several people ordered more books from The Golden Notebook (so can you!)

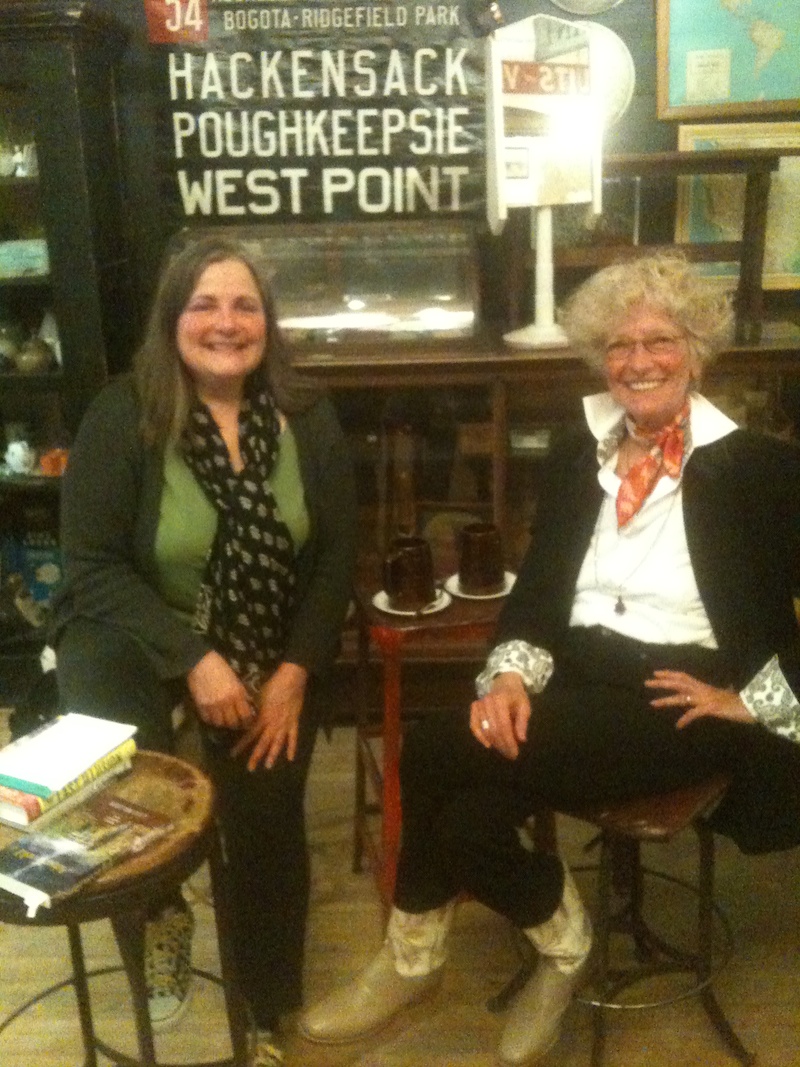

Porochista Khakpour

Photo: Jana Martin

She explained that while Magical Realism usually refers specifically to Latin American literature, Fabulism is a more inclusive term for fiction that combines a magical or surreal conceit with emotional realism.

The first reading Porochista often assigns to her students, at Bard College and elsewhere, is Jorge Luis Borges’ “The Aleph.” along with a Tim O’Brien essay about it.

This helps to combat what she calls “the Wikipedia school of writing,” urging young writers to look beyond the mundane. “We’re all in our individual consciousness, isolated by these weird vessels, our minds. There is no normal,” she said. “The things we dream, that’s surreal. We die. That’s surreal. The extraordinary strangeness of life should be quite germane to us.”

Nina mentioned some fabulist stories she’s taught by Steven Millhauser (“Flying Carpets”) and Karen Russell (“St. Lucy’s School for Girls Raised by Wolves”), and Porochista added more names from what she calls “Team Sorceress”: Kelly Link, Aimee Bender, Laura van den Berg, Leonora Carrington.

POROCHISTA’S EXERCISE:

Choose a sentence from something you’ve written (or invent a new one) that could be the ending to a piece. Now work backwards to the beginning, listing six major events or plot points.

NINA’S EXERCISE:

Write an encounter between two characters that begins in the real world, on earth, and moves into a different element: air, water, fire. See where it leads you.

The minutes-old work people shared in class was amazing. Writers, try these at home! And come to outdated: an antique café on Thursday, 5/7 at 6:30, when the brilliant novelist Pamela Erens (The Virgins, The Understory) joins me to talk about “The Storyteller’s I.”

Lois Walden’s reading from her novel

Lois Walden’s reading from her novel  Gretchen Primack treated a rapt group to a reading of poems in many forms: sonnets, haiku, iambic pentamenter in tercets, a suite of Yiddish-inflected limericks, an ekphrastic poem (i.e. inspired by another art form) and “a form only real poetry nerds will know,” a paraclausithyron, or lament sung through a lover’s locked door. She found this and other deliciously obscure forms in

Gretchen Primack treated a rapt group to a reading of poems in many forms: sonnets, haiku, iambic pentamenter in tercets, a suite of Yiddish-inflected limericks, an ekphrastic poem (i.e. inspired by another art form) and “a form only real poetry nerds will know,” a paraclausithyron, or lament sung through a lover’s locked door. She found this and other deliciously obscure forms in