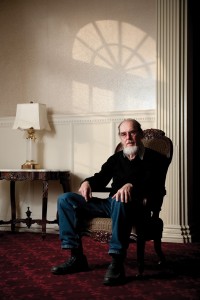

Edwin Sanchez “Making Drama”

May 21, 2015

Playwright Edwin Sanchez gave us a tantalizing and hilarious sneak peek at his forthcoming novel Diary of a Puerto Rican Demigod, along with some wonderfully down-to-earth advice about writing (“You just sit down and do it.”)

Playwright Edwin Sanchez gave us a tantalizing and hilarious sneak peek at his forthcoming novel Diary of a Puerto Rican Demigod, along with some wonderfully down-to-earth advice about writing (“You just sit down and do it.”)

Do playwrights and fiction writers approach their work differently? Not really, says Eddie. “We all have the same box of crayons. We just use different ones for different things.” For him, the joy of writing fiction was getting to go inside a character’s head.

When he teaches playwriting, he asks his students the following questions:

— Who’s the main character?

— What does he want more than life itself?

— What’s stopping him from getting it?

Nina observed that the character’s obstacle can be internal–something he’s scared of or struggles with–an outside circumstance, or both at once. The bigger the obstacles, the better the drama.

Eddie often starts out by writing a monologue for his lead character (“A good monologue is like an aria.”) Then he starts thinking about who’s hearing this monologue and how they might respond. We talked about the elasticity of writing for theatre. It’s a collaborative form, and a script isn’t fully alive until it’s performed. Plays take place in present tense, in real time and space, and no two performances are alike. Different actors and directors may approach the same character in ways that surprise you, for better or worse. But when you write a novel, the buck stops with you. “You don’t get to say it was miscast,” Eddie said.

Diary of a Puerto Rican Demigod is distinctly not miscast.

EDDIE’S EXERCISE:

Write a character’s dream (or nightmare) as a scene, monologue, or poem.

NINA’S EXERCISE:

Write a two-character scene in which one character has something the other wants. What does the second character do or say to get it, without ever coming out and asking “Can I have that?”

As usual, the concentration was intense as a roomful of writers went to work on these prompts. As Eddie and I sat and talked quietly, one of the vintage signs on the wall caught his eye. So here is Exercise #3:

Write a short play entitled EAT CHICKEN DINNER CANDY.

Novelist

Novelist  The Virgins is narrated in first person by someone who uses third person to narrate scenes that he couldn’t have been privy to–Bruce is recreating the story of Seung and Aviva, for reasons that become evident as the story unfolds. This unusual narrative strategy was inspired by James Salter; Pamela named an English teacher at her fictional school after him in homage.

The Virgins is narrated in first person by someone who uses third person to narrate scenes that he couldn’t have been privy to–Bruce is recreating the story of Seung and Aviva, for reasons that become evident as the story unfolds. This unusual narrative strategy was inspired by James Salter; Pamela named an English teacher at her fictional school after him in homage. There were some excellent questions from the group, including a discussion of writing first-person narration from the point of view of someone who wouldn’t have a sophisticated literary vocabulary, for instance a teenager. Pamela’s advice? “Don’t worry about it. The voice of a story is never identical to the voice of a character. It’s a translation of what that character is thinking and feeling. Prose that’s written as we really talk is not that interesting most of the time. Readers will always go with you if give more richness to the language.”

There were some excellent questions from the group, including a discussion of writing first-person narration from the point of view of someone who wouldn’t have a sophisticated literary vocabulary, for instance a teenager. Pamela’s advice? “Don’t worry about it. The voice of a story is never identical to the voice of a character. It’s a translation of what that character is thinking and feeling. Prose that’s written as we really talk is not that interesting most of the time. Readers will always go with you if give more richness to the language.”