WORD CAFE EVENT ARCHIVE

PAUL RUSSELL – PAST & PRESENT, 10/22/15

Novelist and Vassar professor Paul Russell led a terrific discussion of the many roles of past and present in fiction. His just-released novel Immaculate Blue centers on the wedding of longtime lovers Anatole and Rafael. Guests include Anatole’s close friend and Poughkeepsie neighbor Lydia and the elusive Chris, with whom they share a complex past and a love object named Leigh, aka Our Boy of the Mall. They also share another novel: younger versions of Chris, Anatole, Lydia, and Leigh appear in Paul’s first novel, The Salt Point, published in 1990.

Novelist and Vassar professor Paul Russell led a terrific discussion of the many roles of past and present in fiction. His just-released novel Immaculate Blue centers on the wedding of longtime lovers Anatole and Rafael. Guests include Anatole’s close friend and Poughkeepsie neighbor Lydia and the elusive Chris, with whom they share a complex past and a love object named Leigh, aka Our Boy of the Mall. They also share another novel: younger versions of Chris, Anatole, Lydia, and Leigh appear in Paul’s first novel, The Salt Point, published in 1990.

Paul read the opening of Immaculate Blue, set in a changing Poughkeepsie. It’s narrated in present tense, with a swooping point of view that moves fluidly from one character’s thoughts to another; Paul favors “ensemble novels” over the “claustrophobia” of a single first-person narrator. Present tense has the advantage of immediacy–you’re right there with the narrator as events take place–but “can lack a certain reflective depth.” Paul’s writing professor James McConkey posited that literary use of present tense was a response to the atomic bomb; there’s no faith in the future. Past tense communicates an assurance that we’ve survived, and can look back on the events of the story from a safe distance. Present tense gives the feel of a story unfolding from moment to moment; its pace is more hectic than thoughtful.

Immaculate Blue’s wedding and reunion with long-absent Chris gives all the characters occasion to revisit the past in memories and in conversations with each other. Paul pointed out that good dialogue appears overheard, that characters talk “to each other, not to us” in a sort of shared shorthand–they don’t remind each other of things they already know. The reader does not need to get all the facts to be drawn in–in fact, quite the opposite. “We love puzzles,” Paul said. “We love putting the pieces together. If somebody hands you a jigsaw puzzle that’s already done, where’s the pleasure?” Nina added that a writer’s great place of power is making the reader want to find out what happened.

Paul observed that his characters’ versions of their shared past vary in often self-serving ways, so “there is no truth, only perspective.” Though he hadn’t revisited these characters in many years, when his agent proposed writing a sequel to The Salt Point, he caught up with them instantly. “It was as though there was a locked room in my brain where the characters had been living, and all I had to do was open the door.” Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, with its ten-year gap between parts one and two, offered him inspiration.

THE EXERCISES:

— Paul read a short passage from Joyce’s story “The Dead,” in which Gabriel Conroy has an awkward conversation with Lily, a servant girl who answers his small talk about schooling and marriage with “The men that is now is only all palaver and what they can get out of you,” revealing far more of her experience than he expects. Paul asked us to write a seemingly inconsequential encounter between two people in which the dialogue gives a hint of an unexpected history.

— Nina asked participants to think of a place they had been both as a young child and later in life (a relative’s house, a school, a vacation spot). Write a paragraph or section in present tense from the child’s perspective, beginning with “I am standing in…” and a second paragraph in past tense from the adult perspective, beginning with “When I went back, I noticed…” What is the effect of the switch in tenses?

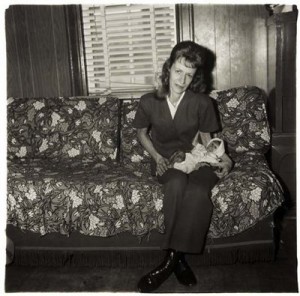

Photo credit: Jana Martin

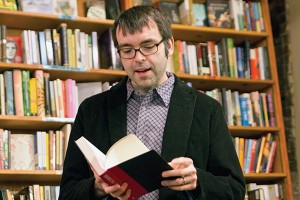

Novelist and graphic novel collaborator Owen King treated us all to a reading from his novel

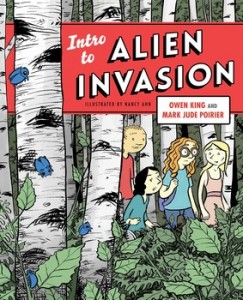

Novelist and graphic novel collaborator Owen King treated us all to a reading from his novel  Owen’s latest book is

Owen’s latest book is