KIESE LAYMON is a black southern writer, born and raised in Jackson, Mississippi. Laymon attended Millsaps College and Jackson State University before graduating from Oberlin College. He earned an MFA from Indiana University and is the author of the novel Long Division and a collection of essays, How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America. Laymon is a contributing editor at gawker.com. Long Division was named one of the Best of 2013 by Buzzfeed, The Believer, Salon, Guernica, Mosaic Magazine, Chicago Tribune and the Crunk Feminist Collective. Laymon has written essays and stories for Esquire, ESPN.com, Colorlines, NPR, Gawker, Truthout.org, Longman’s Hip Hop Reader, The Best American Non-required Reading, Guernica, Mythium, Politics and Culture, and others. Laymon is currently at work on a new novel “…” and a funky memoir called 309. He is an Associate Professor of English at Vassar College.

Read Nina Shengold’s Chronogram profile.

Letters Home 11/13/14 – The Exercises

Dear Word Café family,

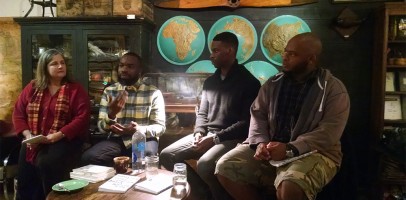

Hard to sum up this powerful evening in words. There was a lot of listening and love in the room as Kiese Laymon, Darnell L. Moore, and Marlon Peterson read their contributions to the essay-in-letters “Echo,” which also includes letters by Mychal Denzel Smith and Kai M. Green. (The full text is in Kiese’s amazing How To Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America, which you can order from The Golden Notebook.

Our subject was “Letters Home.” We talked about how letters foster direct address and one-on-one intimacy; Darnell called epistolary forms “invitational,” and I observed that letters begin and end with words of love and respect (Dear, Love, Bless, Yours truly). While Marlon was incarcerated, he started writing letters to a teacher friend’s middle-school class–he says it meant as much to him as it did to the students, who often wrote about things they’d never felt able to tell their families or anyone else.

We talked about the courage it takes to go deep and tell personal truths. Darnell still gets fierce anxiety when he reveals himself in print, but feels it’s important to connect with others who struggle with issues of mental health, suicide ideation, physical abuse, sexism, racism, homophobia, transphobia. He spoke about building a bridge that invites readers into the conversation, and how a piece that feels vulnerable often gets responses of “Thank you for writing that.” (Here’s an example, just published in Ebony).

Kiese spoke about feeling a responsibility to others whose lives are revealed when he tells his own truth. In the title essay of How To Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America, he describes his mother (a college dean) pulling a gun on him when he was 19. When he showed it to her before publication, she said he couldn’t print that, and even that she didn’t remember it happening. Kiese felt strongly that it needed to be part of the essay, and proceeded “as generously as possible.” They exchanged long letters about what should and should not be revealed, things they’d never been able to talk about in person. “It opened a dialogue. Maybe printing that wasn’t good for my mother, but it was good for our relationship.”

When writing fiction, Kiese sometimes writes letters from one character to another as part of his process, just to get inside their head and get the sound of their voice right.

Marlon talked about the value of writing by hand, and the intimacy of looking at someone else’s handwritten words. He said he often “walks with an idea in his head” for a long time, then sits down at 2am to write it all at once; his letter in “Echo” happened like that.

Kiese said the word “echo” explores the way truths reverberate: “If you really open up, what do others write back?” Darnell talked about creating a “safe, risk-taking space” and “writing to create community.” All three men have collaborated with others on writing projects under the collective name Brothers Writing To Live (from the Facebook page: “We are a group of black cis and trans-men who hail from spaces across the United States. And we write so that we and our people might live.”) He also spoke about men’s involvement in feminism, and the reverberations among disenfranchised communities: “What would it be like if we all stood up and said, ‘This is not right?'”

We talked so long, and fielded so many great questions from participants, that we skipped the usual break and barely had time to start on a writing exercise. But here’s what it was:

— Pick someone in this room you’ve never met and introduce yourself. Sit down and start writing letters to each other. Write about what brought you here tonight, and something about yourself.

If you weren’t in the room, or didn’t get the name and address of the person you’re writing to, write a letter to someone else. And send it. Tell your truth. Connect.

Love, Nina